56 Dean Street clinic manager Leigh Chislett began working on HIV hospital wards as a student nurse in the mid to late 80s, aged 21. He and his co-workers were on the frontline of healthcare services as HIV and AIDS arrived in the UK, and saw many young men die from the illness. Now he’s produced a film, AIDS: Doctors and Nurses Tell Their Stories, where he and former colleagues describe the best and worst times of those years. Photos by Gideon Mendel.

Hi Leigh, I really enjoyed the film. Where were you working at the time?

I started at St Mary’s in Paddington, working on the HIV ward there, and also at the Sexual Health Clinic. That was in around 1987/88. In 1990 I went to work at the Kobler centre at St Stephen’s, now part of Chelsea and Westminster Hospital.

Around the time HIV had just arrived in Britain?

It had arrived. We had hearing about what was happening in America where it had hit a couple of years before and although we hoped not we knew it was a matter of time before we would see people with this virus here. I think it was ’86 when there was a stream of people, but by ’88 we began seeing more people becoming ill and we began realising ‘We have a real problem here’.

How did you feel when you realised that it was arriving in the numbers you describe?

If I can just go back a bit: like many young gay men, I was attracted to London so on a personal level in those early days when people were becoming unwell I was thinking ‘Oh my God – what the hell is going on?’ It was strange: one minute you could be dancing with someone in say in the Two Brewers, and the next time you saw them they had a purple lesion on their arm or had lost loads of weight and you realised they had this strange virus that people were dying from with no treatment or cure or how you caught it it felt surreal and we were scared.

In the clinic we were preparing ourselves, so there was this real tension in the air. They were used to people coming in with gonorrhoea and chlamydia, but then people started coming in with their partners who were struggling to breathe with pneumonia and were seriously unwell. And there was a lot of anger, because parts of the press was so appalling, so there was a big fight on as well.

What moments do you remember about that time?

I’ve always been someone who hates injustice and there was a lot of injustice about. And the press headlines were saying things like ‘Exterminate gays!’ which would be seen as hate crime now, but they were allowed to get away with. These were desperate times and people were dying and these bigots were allowed to vent their hatred.

Dying horrendous deaths, not just slipping away – they were really suffering.

The deaths were often brutal. They were often young men with strong hearts but their bodies just deteriorated around them. You must remember we had no medication for this. We didn’t even really know what was going on. We were sort of having to make it up as we went along. We were guessing it was sexually transmitted, but we didn’t absolutely know.

There was the whole not sharing cups and cutlery…

Oh absolutely, there was a lot of hysteria. But some people were genuinely scared. At the time people with AIDS would get infections like cryptosporidium and they would pass litres and litres of diarrhoea until their body would just deteriorate around them. It was horrifying.

But I don’t want to paint a completely gloomy picture because the camaraderie, the way the gay community came together, was phenomenal. People were being chucked out of their homes for instance and others would offer rooms in their flats. People like Lily Savage and Regina Fong would come to the wards and do a show at Christmas. One thing those times taught me is when people come together you can change things. The LGBT community took on the press and the government and won. For a young man, to see that was amazing; that was gay pride.

One of the contributors on the film [Theresa] said she knew she couldn’t go on working on the ward, because of her own emotional wellbeing. When did you stop working with AIDS patients? Did you have to walk away?

I did from the ward. I didn’t stop working in HIV. My last time on the ward was on a night shift and three patients all young men died on my last night and a fourth patient just before I went off duty who I had become friends with. We had to lay out the bodies. And I turned to my colleague and said “I can’t do this anymore.” I felt terribly guilty, but I couldn’t stop, so I went into HIV outpatients and daycare. I think what sometimes people tend to forget is that some of the guys that were coming in were people that we knew – the gay scene wasn’t that big. And if you hadn’t seen somebody out for a while, there was almost the assumption that they must’ve died. That’s what it was like.

Seeing the effects of AIDS and young men dying, all that at the start of your career, how has that affected you?

Well it’s interesting because if you’d have spoken to me five years ago I wouldn’t have been able to talk about this. But partly by doing the film it’s allowed me to remember it in a different light.

I think like many I suffered some post traumatic stress. But also, looking back, I learnt so much from those guys. My generation was bombarded with the messages that if you were gay you will never have a proper relationship and you’ll inevitably end up lonely, our sexuality was often ridiculed and the message was there was something wrong with being gay.

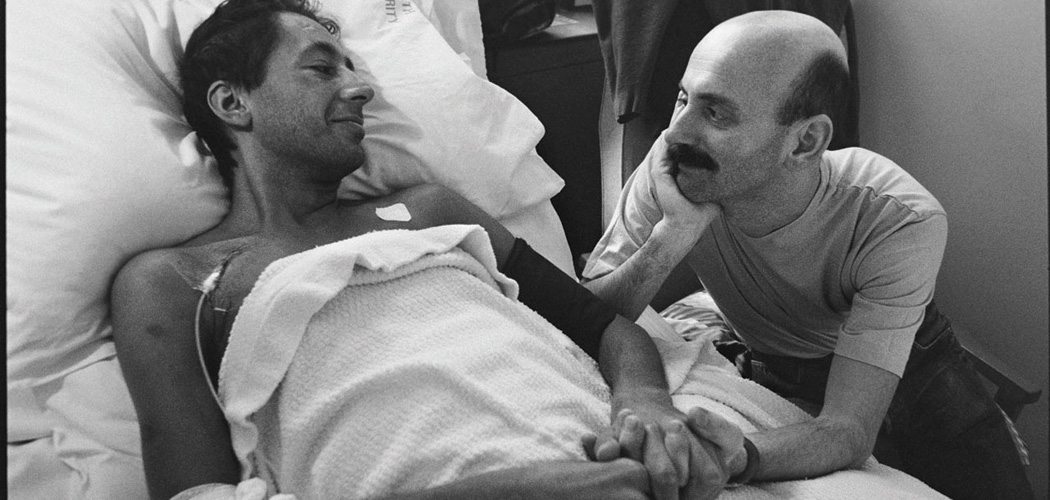

So going onto the ward, I remember there was this guy who was dying – he must’ve been about three stone, he was so painfully thin. His partner was this big muscular guy. He never left his partner’s bedside. He would hold his partner’s head and slowly wash his hair, and gently clean his teeth, like he was made of porcelain. I learned that most I had been told about being gay was a lie – I had never seen anyone love like this couple loved each other.

Total devotion.

Absolutely. So everything everybody had taught me was blown out of the water. So many people I met and worked with were life-inspiring. [Back then] we had a group of people who were losing their friends and lovers, we weren’t going to take crap anymore. In the early days gay men galvanised themselves and fought for better services, demanded that drugs were released and demanded equality – “We want it better!” – and so this experience really motivated me to take sexual health from being hidden basements or the back of hospitals associated with shame, to help set up 56 Dean Street and Express. Of course I didn’t consciously think of this at the time, but looking back it taught me how to fight for things to be better.

In the film you describe the final moments of one man’s life – he was on all fours and it was clear he felt embarrassed and undignified. He then died in your arms. You say you were 21 – how old was he?

In his twenties – 25 or 26. He was a little bit older than me. And I can still see his face. I was very impacted by him. I still after all these years feel very emotional about it.

And how has that moment affected you?

Before then I’d seen a lot of elderly people die, and I’d seen young people die. But with him it was the first time somebody had died in that way with me, and who was so frightened. It was hard because I could not make him better but I hope he died less scared.

Why has it stuck with you so vividly?

I think because it was very emotionally intimate. I had not been on the ward that long and it suddenly hit me that this was going to be tough.

How did the film come about?

It had been on my mind for three or four years and I’d never had the courage to get round to doing it because it’s not easy to revisit that time. I wanted to capture the experiences of doctors and nurses from that time before it was lost.

It seems to have been quite a cathartic experience for you…

Yes. Somebody said to me “Oh what’s this about, your therapy?” And I said, “Yeah, partly, it’s some unfinished business I have to deal with.” But as Corrine, who is in the film, said, it was a such a privilege to be nursing at that time. And Jane, who said it taught her what nursing should be, and I totally agree.

How would you sum up your relationship with HIV?

I think for years I was angry at HIV for what it had taken – I think I had a vendetta against it, but this anger has not been destructive but has motivated me. I was glad I could help in some way. It taught me a lot. It made me grow up very quickly. It politicised me. And I’ve got some very close bonds with the people from that time that won’t be broken.

Treatment has improved so much in the past 30 years, but during my time at Boyz I’ve come across younger guys who are of the mindset that if they get HIV it’s OK, because then they can start treatment and they’ll be fine and still live a normal lifespan. But I’ve always thought that that message, while true, is a little misleading, and that it’s not quite as simple as that. What message do you think should be put out there? Because obviously we don’t want more and more people to get HIV…

No.

So what do you think should be communicated?

Yes, I think you are right… My experience of working in the clinic is that it is not as simple as that. I think medically we’ve come on enormously but psychologically and attitudes towards HIV have not caught up at the same speed. I think it is true to say that most people who are HIV positive would prefer not to be.

What is your message to someone who has just been diagnosed positive?

Try not to panic. You can have a full lifespan. And if you’re finding it tough, we are here to help.

What can you tell us about the possibility of an AIDS memorial…

We’re working on it at the moment. There’s a petition out at the moment to the Mayor’s office for it, but there’s a group of us that want to see an AIDS memorial certainly. We’re going to regroup in the New Year.

For more on the film AIDS: Doctors and Nurses Tell Their Stories please visit www.iridescentfilms.co.uk. The film will be touring in Spring 2017.