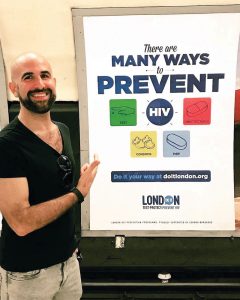

Dubbed ‘the most simple but comprehensive HIV campaign seen in years’, Do It London’s new campaign advocates a range of HIV prevention options. Luke Till asks Paul Steinberg, Lead Commissioner and Programme Manager, London HIV Prevention Programme (LHPP), what impact he hopes this new campaign will have on London’s general public.

Do It London has been promoting HIV testing and safer sex in the capital for two years. During the same period, HIV diagnoses in the capital dropped dramatically, with a record 40 per cent reduction in new diagnoses in five central London clinics. Such a dramatic fall was not observed in the rest of England. How much of a role do you think Do It London has played in realising these statistics?

I think Do It London has contributed in part to that drop in diagnoses in a way that lots of other factors have contributed to it during that same period. When we learnt about the reduction of diagnoses in January when these clinics announced their figures, everyone was very excited. And for those of us who have worked in HIV prevention – in my case for 15 years – it was the first real breakthrough, because for year on year we’d been seeing HIV diagnoses go up in gay men since about the year 2000, and in 2015 there were 6,095 HIV diagnoses in the UK, of which 54% were in gay men. That was despite lots of interventions being funded, including national campaigns, local programmes, increased access to sexual health clinics, testing campaigns. So seeing a reduction in diagnoses we thought ‘Wow, this is impressive.’

When the clinics came out and told us this information, the mainstream press all seemed to conclude unanimously that it was because of PrEP. But actually, when the scientists looked more closely at the data, they saw that the reduction of diagnoses was attributed in part to massive increases in testing rates in gay men. And it was both an increase in the numbers of tests and crucially the frequency of tests, so more people are going back every three to six months and more people are doing that – though we need to increase the number of repeat testers still going forward.

So although the press said it was all due to PrEP, we were trying to say this is more complex and due to multiple reasons. From London councils’ perspective, who fund sexual health clinics and the London HIV prevention programme, Do It London as a campaign had to have played a key role in the story. The campaign itself began in 2015, and more broadly the London HIV Prevention Programme [LHPP] began in 2014, so during that whole period of a fall in HIV we had benefited from a dedicated gay men’s sexual health promotion service that is very scene-based, where outreach workers go out night after night. And we increased the amount of free condoms that are available from about half a million to 1.2 million given out in bars, clubs and saunas every year.

So we had a year of the scene-based gay men’s work, and then Do It London as a campaign kind of appeared out of nowhere across London in the spring of 2015, with its key messages around combination prevention – test and protect to prevent HIV.

And our perspective is: if London councils are spending a million pounds on a testing and safer sex campaign in 2015 and 2016, in a way that has never been done before, and testing rates go up, then of course there’s a significant contribution that has been made there by the LHPP, in line with the other prevention methods that we are promoting and that were delivered by other parts of the sexual health system. It would be both a historical terror and remiss to attribute this drop in diagnoses to one factor alone. In April 2017, the head epidemiologist for Public Health England, a brilliant lady called Valerie Delpech, looked at the data from clinics around London and England, and she presented a paper in Malta to conference that said – controversially, for some people – that the drop in HIV diagnoses was real, exciting and it was based on a kind of organic experiment which was a huge increase in testing and, most crucially, when people get diagnosed positive they get put on HIV treatment very, very early – sometimes within the same week. Whereas a few years ago when you got diagnosed you’d maybe wait six months, a year, maybe even two years. And her theory is that the combination of increased testing and early treatment was primarily responsible for the reduction in diagnoses during that period

Now let’s not forget that I’m a PrEP advocate. Last year when there was the High Court battle between NHS England and NAT, London Councils supported NAT, and I publicly supported the availability of PrEP on the NHS, saying PrEP was a game-changer and a really important part of the tools we have for HIV prevention. But we should all be cautious about attributing a single intervention in HIV as responsible for the amazing drop in diagnoses – it isn’t as simple as that, and it’s risky to think you can just have one thing without another. What Do It London has campaigned on, and is increasingly now campaigning for, is combination prevention, and I keep repeating that everybody has played a role – from clinics to campaigners to commissioners to activists. Do we take some credit? I guess so, in the sense that we have demonstrated a return on investment for the local authorities who fund the London HIV prevention programme. We came along in 2015 and splashed messaging everywhere in London, telling Londoners to get tested for HIV and about the importance of safer sex options – not just gay men, but Londoners in general – and that message wasn’t out there so visibly and so loudly in the capital two years ago.

And this new campaign reflects all that.

Exactly. In January we did the ‘STIs are on the rise’ campaign, which Boyz also covered, and it was probably the most hard-hitting campaign of the four that we’d done to that point. It was similar to our Christmas 2015 campaign, which talked about the importance of condom use too. The tagline for it was ‘Do It with a condom’ which was of course in part driven by the public health science which was showing huge rises in STIs in gay men for the past seven or eight years running. But when we released that campaign some of the more vocal PrEP activists really objected to it, because they missed that it was more an STI campaign than about HIV. And partly that was because we were trying to do too much in one campaign. We are the official London HIV prevention programme, but we had been asked by worried public health officials across the capital to try to do something about rising STIs. And, despite the criticism, it does seem to have worked in part – STI rates fell in 2016 for the first time in almost a decade, with data out last month showing a record 25% drop in gonorrhoea diagnoses in gay men. Public Health England explicitly said that this was thanks to campaigns promoting condoms and screening, so it was worth the flak in hindsight.

Also, a year ago it wouldn’t have been ethical for us to have campaigned widely to promote PrEP, because we’re a government campaign for London and PrEP wasn’t available then on the NHS. Yes, it was accessible to those who can afford £50 a month buying it online, but it wasn’t available to all. But as soon as we knew the PrEP trial was going to be starting in summer 2017, as we were told, it was always a matter of when, not if, it would become part of our campaign about HIV prevention. That means, whilst we’re not going to stop talking about condoms, we’re not going to stop talking about testing, I wanted us to start focusing on the importance of PrEP as it became available through the trial. Most crucially I was adamant that we should start promoting the science behind being “undetectable”, which is no doubt a new concept for average Londoners.

So the new campaign really merges all the science into one campaign, and the response has been really great, from both stakeholders and communities, including gay journalists and people who have been fighting HIV stigma for years. I liked a tweet from someone senior at UNAIDS, which called it the most simple but comprehensive HIV campaign they’ve seen in years. What people have said is that everybody gets something out of it.

And what we’ve seen with social media is people who are pure public health specialists have said ‘we like this campaign because it still focuses on testing’. People who are big condom advocates have said ‘we like this because condoms are still included. PrEP advocates have said it’s great to see the first official campaign in the UK funded by government telling people about PrEP’. And, as importantly in some ways for us, positive people who have often been cut out of the prevention equation are seeing undetectable featured as a new concept, where we’re telling everyday Londoners that the idea that somebody is undetectable means that they cannot pass HIV on to their partner. That’s been pretty groundbreaking and that’s what got us a lot of press coverage so far. I think the U=U campaign, which is a worldwide campaign, and the campaigns that have been done by HIV charities have all been fantastic attempts to make this point but they’ve not been targeted, as we are, at the broad general public. Do It London is on every tube platform, carriage and most buses in the city – so we wanted to get the message out to everyone, regardless of their sexual orientation or HIV status. In the development of this campaign, I remember having a conversation with someone very senior in public health, and they said “I don’t think you can put ‘undetectable’ in a public campaign, people won’t know what it means”. But the very purpose of a public awareness campaign is that when people see the word PrEP or undetectable, and they don’t know what it means, they can either click through on social media and it will tell then, or they can search for it and because of the way we do out advertising, our page comes up as the first result – so they’ll see the evidence that shows that somebody who is HIV undetectable is not able to pass on HIV. So that’s the bit that’s probably the most innovative – if, according to some people, a little daring as well.

You mention that you won’t stop talking about condoms in future campaigns and, as you’ve just said with this new campaign, condoms are given equal weight as an option, alongside PrEP and treatment as prevention. In a world where other sexual health campaigns no longer push condom use, have you been criticised for continuing to promote condoms in this new age of PrEP?

Fortunately we haven’t been criticised for keeping them in, and if we were criticised my response would be “What planet are you on?” Condoms are still being used by lots of gay men, we know from evidence, both within casual and long-term relationships, depending on the context. The other thing is, as part of Do It London, we give out over 1 million free condoms every year and those condoms get taken on the scene – more than 60 gay venues in London have Do It London condoms. So of course we would continue to promote them.

Also, there are still lots of STIs out there and some – though we recognise not all – of them can be prevented by using condoms. For me, good sexual health is also about trying to limit the negative impact that can happen from sex when it comes to STIs as much as HIV. Having worked in sexual health for many years, I’ve seen the anxiety and problems that can come from even getting a chlamydia diagnosis, and we shouldn’t underestimate that. We want people to have healthy, fun, safe and enjoyable sex lives, and in some contexts using a condom will be right, in others of course making an informed choice not to use one but to rely on another prevention method will be equally valid. That’s why the tagline of the new campaign is: do it your way.

And I think it’s really important that an official campaign validates those multiple choices as legitimate and still relevant, rather than seemingly imply that condoms are ‘old’ or ‘over’ by omission. Ask any clinician and they’ll still recommend condoms as a key part of HIV prevention and sexual health promotion, but what we are saying is that there are these other elements that work too.

Sometimes, this work can get very personal. I am a gay man, in my thirties, and so I have experienced some of these issues first hand. I also have friends who are in serodiscordant relationships and they have made decisions not to use condoms because one of the partners is HIV undetectable, and that’s a really valid and affirmative choice in that context – though of course they still sometimes worry as we have had over thirty years of massive, deep-rooted fear of HIV. So if a friend was going to Sitges tomorrow and didn’t have time to get PrEP, but has tested negative and really prefers not to use condoms, I would say to them that they need to weigh up the choices and make an informed choice about preventing HIV and other STIs. The campaign is fundamentally about empowering people with the knowledge to make those informed choices in the first place. Professionally, I always have to remember that we are campaigning for a wide audience, including the 18 year old guys arriving in London this month to start university, who perhaps haven’t had sex and relationships education, who are downloading dating apps and being bombarded with opportunities to do all sorts of things that can be fun, but which might leave them confused about safety. It should be all our community’s duty to educate and empower them as to what is and isn’t a risk.

Which areas of the community are you still finding difficult to reach?

We have three target groups: the general London population, which is almost nine million people potentially; men who have sex with men [MSM]; and black African men and women. And our evidence shows that over the last couple of years the Do It London campaigns have landed well really well and have changed the behaviour of gay men and of black African men, and that’s because we think our strategy and approach to campaigning for those groups has been to do it completely differently to how it was done before. But I think we’ve still got a job in reaching black African women who are often cited as being one of the hardest to reach groups in HIV prevention work.

Having said that, I’m really pleased to see that this campaign seems to be resonating with sections of the gay population in London that I think used to ignore our previous campaigns or thought they were a bit old fashioned. So we’ve seen a lot of exciting support from well known positive activists, from PrEP activists, but also from general gay men in London who are seeing the advert on the Tube and tweeting things like ‘Wow, so great to see London campaigning bravely on PrEP, undetectable and condoms in one campaign.’

There’s been a huge increase in PrEP use among gay and bi guys over the last couple of years – most have been buying it privately online – and this month the NHS PrEP trial finally started. Guys who use PrEP are generally less likely to use condoms. We also know about the rise of so-called ‘super-gonorrhoea’. So, as PrEP use increases, do you think there will be an increase in diagnoses of other STIs like syphilis and hepatitis, creating a potential time bomb for sexual health clinics in the future?

Nobody knows exactly how many gay men in London are using PrEP. We think it’s a significant proportion but it’s hard to know for sure until the NHS trial begins. It’s delayed, again, but we expect it to start in October.

Are people using fewer condoms when they’re on PrEP? We don’t know for sure, but some evidence suggests yes. The theory of course is that PrEP is another prevention tool that is not meant to replace condoms but enhance prevention. Having said that, it’s understandable that if you’re taking a drug that is proven to be effective to prevent HIV, and if HIV is the main thing that you want to protect yourself against, that using condoms might inevitably become a secondary method; I think it’s absolutely human to think that and of course, for HIV prevention, the science is overwhelmingly strong to support that method.

But you’re right, there have been a number of cases of so-called “super-gonorrhoea” in this country. There’s also been a reported number of cases of hepatitis C infection in HIV negative men, which was generally more associated with HIV positive men, and there’s some concern that this suggests that safety behaviours are changing as a result of condomless sex among men on PrEP.

But – and here’s the bit that we call an organic experiment – evidence from other cities around the world has shown that PrEP, in conjunction with regular testing and good sexual health awareness, is causing a huge downturn in HIV in gay men like never before. And some London clinics are reporting that men on PrEP are testing for fewer STIs than might have been expected because they’re screening for STIs so regularly.

So in an ideal world, even if condom use were to go down, STIs would be picked up at these regular screens, treatment would remove the infections from the community “pool”. And rates would plummet from the knock-on effect.

My main concern is about the ability of the system to cope, because there has been a rising demand for sexual health clinics, particularly amongst gay men, over the last few years, and there is not only a limited, but a shrinking budget to fund those clinics. In 2015 the public health budget to fund sexual health clinics was reduced after the election by £200million, and every year between now and 2020 that budget is being reduced again by on average 3.9%. That inevitably means we have to change the way we deliver sexual health services. The big question, which you’ll have to ask me again in a few months, is can the system cope with an ever-growing increase in demand?

That was my next question! Well, very close: how are sexual health clinics in London coping at the moment?

I think they’re doing their best. We are fortunate to have some of the most brilliant clinics – and clinicians – working in sexual health in the whole world. But there have been plenty of stories in the press lately about the reduction in sexual health budgets creating a so-called “sexual health time bomb”. But the reality is that we – commissioners, public health specialists, clinicians and local politicians – are genuinely all in this together against a shrinking public health budget that’s comes from government and which could stop being “ring fenced” from as soon as 2019. So your readers will recognize that, with a limited budget and a very stretched system that makes prevention even more important!

It may be easier to test and protect against HIV than ever before, but hooking up and having sex seems to have become more difficult at times. For example, two guys interested in one another speak on an app: one guy is on PrEP and doesn’t want to use condoms, the other is not on PrEP and does want to use condoms, and so they don’t meet up. If PrEP didn’t exist, and assuming the first guy has always wanted to protect himself, he would’ve used condoms before PrEP existed. Furthermore, condomless sex can still be viewed by some as ‘reckless’, and some guys on PrEP can be ‘slut shamed’ online and accused of having STIs. Has PrEP divided the gay community?

That’s a really good question. I think that PrEP is doing some amazing and quite radical things in the community, but again with some unforeseen consequences. In America, where PrEP is more widely available because the company that makes it has subsidised it for at-risk communities, it is more common to see ‘negative, on PrEP’ on guys’ profiles. Over there, I think, ‘slut shaming’ still goes on but it’s far less common than it might be here.

In the UK, until PrEP becomes more widely available, I think there might be a disbelief that people really are on PrEP, whilst ignorance about what PrEP is and how effective it is remains. There’s also this sense that because someone’s on PrEP they automatically won’t use condoms, which of course isn’t true.

Then again, I really think PrEP has done interesting things to unify sections of the community – you can see that in the universally positive response to our new campaign. One of the fantastic things about PrEP is that actually it’s broken down the barriers of stigma and suspicion between positive guys and negative guys somewhat. Whereas in the past, serodifferent guys might have had huge anxiety about having sex, even though the positive guy could’ve been undetectable, I read a lot about that changing in the age of PrEP. It has taken away a lot of the anxieties men have about sex, whether that’s with or without condoms, and that can only be a good, healthy thing that is good for the individual and for our communities.

What we’re trying to do with our campaign is to say that PrEP is a valid choice for all sorts of people.

Of course there is still a lot to do, even when the trial begins. PrEP advocacy needs to do more work to challenge the idea that PrEP is associated with promiscuity. We need to do more to get PrEP to people who don’t know about it, or don’t think it’s for them, including minority ethnic gay men – and women too. PrEP is a prevention tool. It shouldn’t be associated with moral judgment about the number of sexual partners someone does or doesn’t have. And to go back to your example, it’s all about – as it was always about – having a conversation about sex. Just because one guy is on PrEP and the other isn’t and is pro-condom, there should still be a sexual negotiation. We should never lose the idea that negotiating safer sex is a conversation and a mutual, respectful approach is the key to pleasurable and healthy sexual experiences.

Part of combination prevention is also having the knowledge, the will and the control to say “I want to have this type of sex, you want to have this type of sex, we really fancy each other, so how can we have the type of sex that we both want, that we’re both comfortable and happy with?” So maybe your example will seem less starkly intractable over time as people understand more about respecting other people’s choices.

While medical advances in HIV prevention are always welcomed, recently it’s felt like these advances have been coming at a speed faster than changes in people’s attitudes are able to keep up with. For example, we know a positive undetectable person is at no risk of transmitting the virus when having condomless sex with a negative person. But some people will still find it difficult to take that risk, because they’ve had condom use drilled into them for several decades. How do you see this unfolding?

It’s a good point, and not only have they had condom use drilled into them for a number of decades, but also the idea that somebody who is HIV positive is dangerous and risky. It’s interesting that you say the science has been coming almost too thick and fast almost for attitudes to change. Actually the science that somebody who is undetectable is uninfectious goes back to 2008. And it’s taken nine years for UNAIDS to come out earlier this summer with a firm statement that said people who are undetectable can’t pass HIV on, because scientists understandably work with definitive evidence.

As with everything, HIV prevention messaging needs sustained and evidence-based information, education, awareness and campaigning. You can’t tell people a really radical, new piece of information once and expect that to shift both their opinion and public opinion in an overnight way.

What I’m trying to do by putting this in the Evening Standard and Time Out and on the Tube and on buses and trains, is to say this is relevant for you – whoever you are, gay or straight, old or young, in a relationship or single. We’re trying to get HIV prevention back on the agenda of all Londoners and let them decide how to use the factual evidence we are presenting.

I think sustaining this new information is the only way we’re going to change attitudes over time.

Find out more about combination prevention at doitlondon.org