Paul Steinberg is the Lead Commissioner of the London HIV Prevention Programme and heads the Do It London campaign for the London Councils. David Bridle spoke to Paul about the Fast-Track Cities initiative’ target to reach zero HIV infections in London by 2030 and what the challenges are.

The number of gay men newly diagnosed with HIV in London has dropped by 44% from just over 1,400 in 2015 to less than 800 in 2017. Why is the fall in HIV so marked in London?

Even before Do It London came along, London had been spearheading lots of initiatives around testing. When I came back to the NHS in 2009, the first project I was involved with was in Lambeth and Southwark around testing new registrants to GP surgeries. We’ve got some excellent clinical services in London; our sexual health clinics are world class. That’s not just limited to Dean Street, there’s Burrell Street, Mortimer Market, St Mary’s and so on. What’s also happened is that in 2013 councils became responsible for prevention, testing and diagnosing HIV. In those first couple of years the councils radically changed how services were offered; they worked with the NHS and the voluntary sector to change how we do things, because they inherited a situation which seemingly was an upward curve of new HIV infections that was out of control. So it’s really interesting to be sitting here in November 2018 saying ‘Can we maximise this momentum to continue all the way downwards to zero?’. 5 years ago, we were having conversations about ‘Can we even stem the tide?’.

Do you think the ambition of getting to zero new transmissions amongst gay and bisexual men is realistic?

I do, but I think it’s contingent on resources. It’s contingent on sustaining some of the things that we know are effective. Scaling up some of the things we know have been working over the last 2 or 3 years – and in fact probably been working over the last 4 or 5 years but we didn’t start to see the impact until 2015 – but it’s also contingent on us deciding to do less of some of the things we know that don’t work. I would also add it’s not just an ambition to have zero new infections in men who have sex with men – but for London, it is to have zero new infections in everybody by 2030.

What are the things that have worked?

What we’re seeing now is the consequence of the huge, massive increase in testing that went on probably from around 2010; what’s called the ‘test and treat’ model. The other thing which changed was that in 2011 if you were diagnosed HIV positive in a clinic in Soho, you would probably wait between 90 and 100 days before you started treatment. Now, since about 2015, it’s an average of about 30 days. In gay men the distance between infection and testing is quite short compared with some other groups. That means we’re testing them, and then by getting them on treatment within a month rather than 4 months, we’re reducing the viral load, and helping them to become less infectious and ultimately undetectable. According to Public Health England those two – the testing and the early treatment – have been the main drivers of this reduction in new diagnoses in gay men.

What part has PrEP played in reducing new infections?

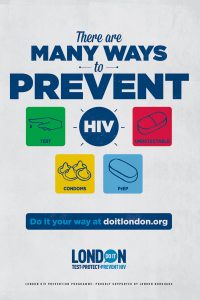

Public Health England (PHE) were quite explicit in their report last year, and their September 2018 report, that it’s too early to tell the impact that PrEP’s had, and their epidemiological evidence was that it was mostly testing and treatment. That riled some people because it seemed to negate the growing impact that we think PrEP has had. What PHE have said subsequently is that they weren’t negating the impact of PrEP. It’s absolutely evident that PrEP is playing a role, but there’s not yet strong robust evidence on a population level this is having an impact. But, as Do It London campaigns have said since 2017, if we combine methods – testing, early treatment, undetectable status and PrEP – and that’s what’s making the impact.

What were the changes made by local government which has made it more effective as a sexual health service?

There were probably three key things: Firstly, the reconfiguration of sexual health services and changing the way clinics and services were commissioned in terms of the hours that they worked, the number of tests they offered, moving to quicker and rapid testing, and that was in partnership with the clinics.

Secondly, at the end of 2015 the home sampling service went live so suddenly instead of having to make an appointment, wait in clinic to be seen, even for a 30 second test; suddenly the whole ‘You can do it at home’, you can test at home, became a real possibility. Then home testing where you can do the test at home and get the result there and then had become legal, and tests became available in early 2016. So the access to testing massively increased.

The third thing was in 2014 councils in London came together to form the London HIV Prevention Programme which created Do It London, which was the first London-only big publicity campaign about, at first, the importance of HIV testing, and now PrEP, undetectability and the other combination prevention methods. And you hadn’t had a London-only HIV prevention campaign, in public spaces, for everybody, like that, ever – or certainly not since the 1980s.

Can you tell us more about Do It London’s work on the gay scene?

For gay men, Do It London has not just been about the campaign, but has been about taking HIV testing into the scene, day in, day out. That’s been a really key element of it because instead of just relying on people to come to clinics, or ordering kits at home, we’re taking the tests to bars, clubs, saunas, nightspots. I commission voluntary sector providers, the GMI Partnership, to do that work and people send them really nice emails and Grindr messages saying “Had it not been for you being there in that sauna that night, I would never have tested.”

What’s really interesting about the epidemic in London is that a large proportion of gay men who are diagnosed with HIV were not born in the UK. These are people who probably arrived in the country in the last 5 to 10 years, generally from Eastern Europe and South America and we think they were infected here, and they’re being tested here. So they’re not socialised into how the NHS works, they’ve not been around for all the old campaigns, they may not even identify very strongly as a London gay man – but we are reaching them. But the unifier is they do use the apps, they probably use some parts of the scene like the saunas and sex venues which is why the work we’ve done over the last 4 years with our partners on the scene is really important; the venue managers, the bar staff who let Do It London in, have been so important.

What are the hurdles to getting to zero transmissions of HIV in gay men in London?

One of the key strategic things we need to do is to reduce the amount of undiagnosed virus in the community, and the only way to do that – which is to effectively switch off the source of new infections – is through maintaining and increasing testing and maintaining people on treatment, early and sustainedly. Do It London said as part of its 2016 campaign: “I do it every 3 months”. One of the challenges about having a ‘National Testing Week’ once a year, is that whilst it’s fantastic to remind the general public to test annually, for gay men, only getting tested once per year isn’t enough, especially if they have lots of sexual partners. They should get tested 3 or 4 times a year. Being on PrEP also means needing to test quarterly. So that’s why we have our campaign in the Spring and Summer months to remind people of the importance of testing not just in November, but also when you change sexual partner and at other times of the year.

So we have a bit of a challenge – we need to increase the frequency of testing; we are seeing more people come forward to test for the first time, but we need to make sure they come back. It is an ambitious target for 2030 to have zero infections, which is the Fast-Track Cities initiative’ target the Mayor has signed up to: zero new infections by 2030, zero stigma and living well with HIV.

What are the future plans for Do It London?

The good news is that all London council leaders have just signed up to extend the London HIV Prevention Programme’s funding until 2022; that’s the Do It London campaign, the outreach, the free condoms scheme and the testing. I have to say those council leaders are Conservative, Labour and Lib Dem; they span the colours of the political spectrum. They came together, they saw that HIV is a big issue, and because we’ve been able to show them the progress in reducing HIV infections in London, they’ve pledged to continue to invest for 3 more years at least, because we’ve got this ambitious target of zero new infections by 2030.

For more information about the Do It London campaign go to doitlondon.org