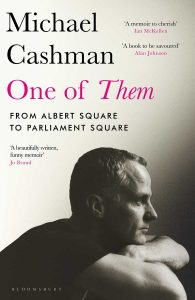

Actor, LGBT activist, former Labour MEP and now life peer Michael Cashman is probably best known to Boyz readers for his role as the gay graphic designer Colin Russell in the BBC soap Eastenders. This month Bloomsbury publishes Michael’s autobiography One of Them: From Albert Square to Parliament Square.

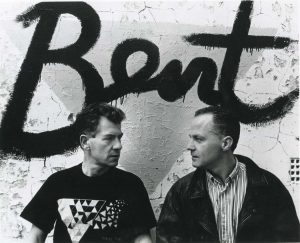

Michael lives in the East End of London, a stone’s throw from where he was born, and where David Bridle met him to talk about his book, his 31-year long relationship to his partner Paul Cottingham, an acclaimed actor, singer and charity supporter, who died in 2014 – as well as about traumatic experiences whilst a child actor in the musical Oliver, the battle against Section 28 and co-founding the campaigning group Stonewall.

Michael, can we start at the deep end, what was it like to go back to those very traumatising experiences which you had as a child, particularly the sexual assault by a local docker, in order to write your story?

I think the easiest answer to that is because of Paul’s death, I had to face my life as it actually was. That profound grief that I carry because of him made me realise that if I was going survive this that I had to deal with all of my demons. When I wrote it, I remember sobbing – not crying – sobbing about what had happened to me, so young – and how I’d manage to bury it for so many years. It was difficult, it was hard, but it was absolutely necessary, if I was to write the kind of book that I wanted to write, which was warts and all.

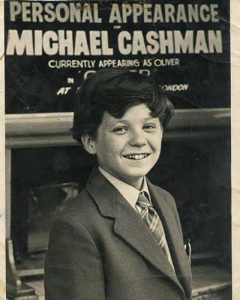

Can you tell us how as a child actor, in shows like Oliver in the West End, you were subjected to grooming – as your own gay sexuality developed?

I think the really upsetting thing was I knew that I was attracted to other boys and when I look back I thought, “Did I have an invisible sign on my forehead that said ‘Abuse me, I won’t tell anyone’?”. And so when I went into Oliver at the age of 12, having hidden my attraction to other boys, I was suddenly in a world where I could be myself. I belonged. Because it was a show about young kids and wayward kids, it attracted a lot of men who hung around the stage door. They would strike up conversations and you would tell them, not so politely, what to do. I was attracted to a guy who was four years older than me, Chris, who understudied The Artful Dodger, and increasingly I fancied him. I was 12 and I didn’t want to waste any time in this new world.

How did the grooming start?

Chris introduced me to a man who must have been in his late twenties called Woody, and I was led into the world of grooming where I was groomed and abused for years. Then I worked on a major film where it happened again. I was quite literally passed from one to the other, but because of what happened to me, I think when I was seven when that docker sexually abused me, I’d found a way of feeling that it was happening to somebody else. I know that may sound strange but a lot of these men were powerful. Directors, actors – so I just went with it, but also deep, deep down I wanted to belong. I wanted to be loved. Dealing with these things is my way of saying no matter what happens to you in life, you can become yourself. But you have to own what has happened to you. You can’t bury it.

Can you tell us about meeting your life partner Paul Cottingham? You’re working in Alan Ayckbourn’s theatre in Scarborough, Paul is a Redcoat in Butlins and appears to be pretty straight. It is an extraordinary love story…

Thank you for saying that. It is an ‘extra-ordinary’ love story, that should never have survived. I’d written a play and I’d gone up there at the insistence of the amazing Peggy Ramsay, a literary agent. We all got an invitation at the end of the season to go to Barbara Windsor’s The Grand Soirée. It was called The Grand Soirée because it was at The Grand Hotel Butlins. I went and there was this young Butlins Redcoat – who delivered the tickets to the theatre a few days earlier – and who I’d spotted in a photograph outside the hotel, thinking “God. He’s gorgeous!”. So there I was in this strange heterosexual globe of the Butlins hotel, and suddenly there at my elbow was Paul and he said, “Hello, you’re the actor from the theatre, aren’t you?”. And I looked at him and there was something about this smile, these eyes that sparkled, this confidence that just drew me in. It was magnetic.

And, as you write in the book, he was pretty straight?

It was clear to me by the end of the evening that this man was heterosexual. At one point, when I was talking to him, this mad woman threw herself at me. She said, “This is MY Redcoat” and dragged him off. And when he came back I said, “I’m sorry, I didn’t know you belonged to someone.” He said, “I don’t, and certainly not her, her husband’s a copper!”.

So Paul had very little gay experience at that point?

We went back that night – and he seduced me. I thought this shouldn’t be happening with a straight man, not even a straight man with more than six pints of lager. And in the morning, he was still there. That night we made amazing love and in the morning when I woke, I thought he hasn’t rushed away. He’s still here. But it was difficult because I think he’d had two or three gay experiences in the previous three months, up until then he was rampantly heterosexual. Coming from a small town in the Midlands, being fearful of what people will say if they found out he was gay, that perhaps his roommate in Butlins wouldn’t want to share with him any more.

The age of consent was still 21?

The relationship was illegal. He was 19, I was 33. I thought this won’t work. Him from a different world, a different community and a me happy, if single, in mine. Then he took the most amazing courageous leap to come down to London. I remember years later Barbara Windsor saying to us, “What is it about you two? I’ve had two husbands since you’ve been together!”.

What was it about you two…?

I think if I’m honest, I think it was his determination not to let go. I’ve always been the first to leave, and it was his determination to continue, his determination to work through it, his determination to see through my darkness.

Did you share much of that with Paul?

Not enough. He knew me better than anyone – and I include my entire family – and because of that I could tell him anything. He could tell me anything. To be able to say to someone exactly how you feel and what you’re going through and what you’re worried about. If it wasn’t for Paul I would not be where I am. I could never have done what I did.

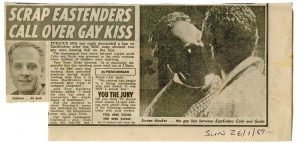

How do you look back on your time as Colin in Eastenders? You had very nasty press coverage which you cover in the book, but at the same time it was an absolutely pivotal moment for gay people watching TV.

It was was pivotal for me. I never knew what I was letting myself into when I said yes. We weren’t aware of what was going to happen to our relationship and the way the press would treat it, but when I look back on it, I look back on it with two emotions: amazing fondness, and amazement at what we did. What the BBC and me and Gary Hailes who played Barry, did. The media world for LGBT people in particular was vile. They used anything to attack us. They accused us of paedophilia. Then when the HIV crisis came along instead of giving us support and understanding they attacked us and stigmatised and misrepresented it as the ‘gay plague’.

Tell us more about your character Colin?

The fact that EastEnders decided to bring a gay character in, an ordinary man who sometimes was so ordinary he could pass on a magnolia landscape without being noticed. He was a west London graphic designer, son of a builder. And for the first three months no one knew his sexual orientation – a brilliant stroke by the writer Tony Holland – and then when it was revealed the press reaction was awful. The fact that we had the first gay kiss and the furore that it caused. Questions in Parliament, letters to the BBC that this character should be withdrawn. When I went into the show there were questions in Parliament: “Why are they bringing a homosexual, with AIDS and HIV swirling around the country, into a family show?”.

And then along came Section 28?

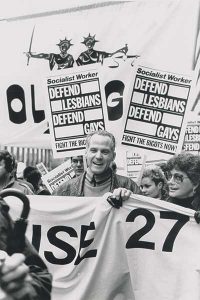

I read in the gay press that Section 28, the first anti-gay law in a hundred years, was being introduced – and there was going to be a march against it. We all get these moments in our lives when you know you have to do something and if you don’t do it, then you will never be able to look at yourself in the mirror again. I’d been in Eastenders about 18 months. There’s a lovely story in the book about how I managed to get on the Section 28 march, and without June Brown who played Dot Cotton, maybe my history would have ended quite differently.

Tell us more about the Section 28 battle…

It was the first march against Section 28. There were about 12,000 of us. We campaigned within the political establishment and we lost the battle against Section 28 and with hindsight, I think if we’d won, I don’t think we would have set about trying to achieve equality as soon as we did. I think there would have been a complacency that really everything was okay but what that did was wake us all up to the fact that we had no protection in the law. That we weren’t equal, that you could be sacked, you could be kicked out of your house, you could be vilified as there was no such thing as homophobic hate crime. There wasn’t an equal age of consent and if you tried to pick someone up on the street you could be arrested for ‘soliciting for an immoral purpose’. These were ‘crimes’ that the arrests were on the increase, they weren’t on the decrease.

How did the seed of campaigning group Stonewall start?

The seed of Stonewall started in the agony of defeat of Section 28. I remember going home and as always in defeat, I was dark and I was angry. I went down to see Ian McKellen one Sunday morning because we live so close, and I talked to him about it. I said come on, we’ve got to set up an organisation because there are people that we’ve connected with that I’m sure would come with us. To a lot of people Section 28 signalled censorship, censorship in the arts, censorship in academia. The following Sunday, he rang me and said, “Come down I want you to meet Douglas Slater.” Douglas worked in the government’s Chief Whip’s office in the Lords, and Douglas just sat there and outlined a very similar idea. And that was the day, it was about two weeks after we lost the battle against Section 28.

When did you first get actively involved with the Labour Party?

I got actively involved in the Labour Party in 1975. An activist here in Limehouse said, “Come on I hear you down the steam baths talking politics, you should join the party!”.

What made you want to become an MEP?

I love the concept of belonging to something bigger. When somebody came to me and said come on you should go into elected politics, I thought no, that happens to others. I didn’t go to university, but it was Glenys Kinnock who said, “The difference with us is we bring a lifetime of different experience from politics.” And I think we need that more and more. Careerism in politics I don’t think serves anyone, not even the person. I think, go out, get your hands dirty, do something else. Know the way the world functions. I don’t take for granted the fact that I’m in the Lords. I know it can all disappear in an instant.

What politically are you most proud of achieving?

Being part of a small group that helped to stop a 17-year-old Iranian student going back to Iran where he would have been hung by his neck until he was dead. Mosleh came out during his application for asylum here in the UK. It was a Labour government and there was some question as to whether he would get that right to remain. When Ed Miliband offered me the job of global LGBT envoy if he become prime minister, I would have been the prime minister’s representative to travel around the world on LGBT issues. I did that for a while under Jeremy Corbyn and then eventually resigned when I no longer had any confidence in the leader to lead the party.

You’ve now left the Labour Party?

Sadly I left after 45 years of membership over the anti-semitism. Then the final straw that broke the camel’s back was in the run-up to the European elections where we were still trying to face both ways on the single most important issue facing this country. I still sit on Labour’s benches in the Lords because I signalled that I haven’t left the Labour Party, the current Labour Party has left me.

Are you following the leadership election?

I am yes. I won’t have a vote, of course. I hope the party does the sensible thing.

Who would that be?

It would be Keir Starmer. And Angela Rayner or Lisa Nandy, and that we begin rebuilding the trust with the British people and we get rid of the divisions.

Where did you write the book?

I took the book off to the old farmhouse that we’ve got in Turkey and I would go for long walks in the morning and go swimming and then come back and sit and write for four hours every afternoon. Thinking about the author’s notes and the direction that Alexandra Pringle, the publisher of Bloomsbury, had asked for. If I had to sum it up, Alexandra would say, “Don’t tell us what to feel, show us.” It chimed because I think the best acting is when you pull the audience in and the audience feel for you. Alan Ayckbourn brilliantly said to me once, “What is more moving someone crying or someone trying not to cry? What is funnier someone laughing or someone trying not to laugh?”. And I got it and that has been with me throughout.

Ian McKellen is this amazing person for you right from the beginning of the book and up to today…

I tried to seduce him back in 1976! He didn’t even notice. He’s the only person I said, “Have a look at the book, if there’s anything you want me to take out, I will.” And there wasn’t anything. We go back to 1976, but it was interesting that we didn’t really get on then. We met at the Royal Shakespeare Company and he completely misjudged the situation. I won’t tell how because it would take the reader away from a nice little nugget in the book. What was interesting was what brought us together and bonded us was Section 28. At the beginning of that Ian wasn’t out. He came out during the process – again I deal with that in the book. Then when Paul died, Ian was incredible, and remains so. A few weeks before he died Paul took Ian aside at a party and said, “You will look after Michael, won’t you?”.

The details of Paul’s illness are heartbreaking in the book. It must have been a shattering experience for you personally.

It’s an experience I live through every day. It was immensely painful because you realise you had no power whatsoever. All I could do was to be there to support him in those interviews with him and his doctors. I was the wallflower. There was misdiagnosis not once but twice. And watching him grow into a warrior, he took on the battle and that was amazing for me.

And at the very end, there seemed to be an acceptance by Paul of what he was facing?

That was the most incredible thing to happen. I knew he was dying. I knew that it was a matter of hours and in the morning when we were told, and we were left alone in that room in the hospital and he said to me, “I’m ready. I’m ready.” The fact that he was telling me he would face death without fear was the single biggest gift anyone could ever give me. And also what it does is when someone you love more than yourself dies, they take away your fear of death and your fear of life. That’s the amazing thing about having written this book. I can’t believe I’ve written it. When I came home with it the other day, I walked along Limehouse Causeway, just past Three Colt Street where I was brought up, and I thought of that little me, that five year old running down that street. And I had the book tucked inside my jacket because it was raining. And I sobbed, and I sobbed, and I sobbed and having finished that book, and Paul having died, no one can hurt me again. No one and nothing.

After Paul had died you write in the book about a sense of self harm and addiction to self-abuse, and you sought out help?

When Paul died, I went through a dark, dark period. And I knew I was getting into a spiral that was going further and further down. I began to realise that I had to deal with all of the abuse that happened to me. All the self-abuse, my addictive personality, my predisposition to falling in love and to walking away, my lack of worth. I would recommend anyone to do counselling or therapy to be able to talk and unburden yourself for an hour without having to think or hesitate about what that person will feel. It was amazing.

One final question Michael, what would you like Boyz readers to take from your autobiography?

There is no other way to do it than to do it your way. It’s your life. Love it, spend it, use it, because in the blink of an eye it is gone.

One of Them: From Albert Square to Parliament Square by Michael Cashman is published by Bloomsbury on 6 February.